Researchers from the CENIEH have analyzed the faunal remains at the Abrigo de la Malia site, revealing successful subsistence strategies among human groups that were highly knowledgeable about their environment. The findings challenge the idea of a population void in the interior of the peninsula 36,000 years ago.

Knowledge about the first settlements of Homo sapiens in the interior of the Iberian Peninsula at the beginning of the Upper Paleolithic has been significantly advanced with the publication in the journal Quaternary Science Advances of a study led by Edgar Téllez, a researcher at the Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH). The study addresses the subsistence strategies of the first settlers of the Meseta through the taphonomic and zooarchaeological analysis of the faunal remains recovered at the Abrigo de La Malia site (Tamajón, Guadalajara).

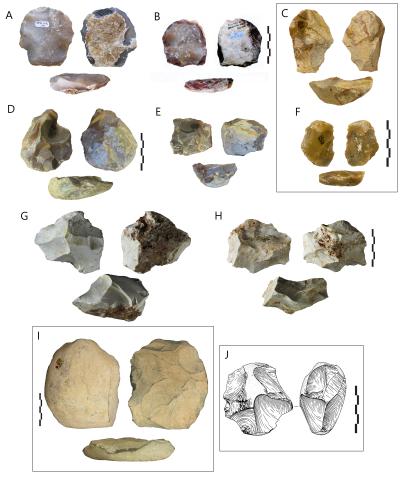

Analysis of animal remains demonstrates that the site, dated to around 36,000 years ago, was occupied recurrently for at least 10,000 years, in a context of constant climate changes. The human groups that visited it mainly hunted deer, wild horses, bison, and chamois, typical resources of forested, mountainous, and grassland environments. Their occupations were brief in nature, meaning the site was not used as a permanent camp. Instead, their visits were likely related to hunting, provisioning, and the initial processing of animal resources.

Human groups in the region, highly knowledgeable about their environment, were capable of developing effective subsistence strategies, based mainly on hunting and processing medium and large ungulates. These practices allowed them to adapt to the harsh climatic and environmental conditions of the Meseta during the initial Upper Paleolithic.

As the authors point out, although human communities faced complex and even hostile climatic environments, the region offered sufficient resources to ensure their subsistence, and these communities knew how to take advantage of them. Therefore, they question the idea of a population void in the interior of the peninsula and challenge us to rethink the mobility, occupation, and adaptation patterns of the first Homo sapiens in the region.

A little-explored region

For decades, it was assumed that the Meseta was left almost uninhabited after the disappearance of the Neanderthals and was not resettled until the end of the Last Glacial Period, about 20,000 years ago, with the arrival of the first anatomically modern humans. In contrast, the Mediterranean, Cantabrian, and Atlantic coastal areas concentrated the majority of known deposits and studies on subsistence practices, providing a solid comparative framework.

The new findings in the Meseta, a little-explored region, are especially novel, since they force us to rethink the traditional models of occupation and adaptive strategies of the first Homo sapiens.

Funding

The excavations in the caves of Tamajón are made possible thanks to the financing of the Junta de Comunidades de Castilla la Mancha through annual calls for the excavation and research of Archaeological and Paleontological heritage, with the support of the Ayuntamiento de Tamajón and G.E. Abismo. This research has also been made possible thanks to funding from the European Research Council (numbers 805478, 949330, and 881299), CENIEH, and the European Research Council (ERC).

The Instituto de Arqueología-Mérida, the Universidad Complutense de Madrid, the Institut Català de Paleoecologia Humana i Evolució Social (IPHES), and the Universidad del País Vasco also contributed to this research alongside CENIEH.