CENIEH participates in a study from the Namorotukunan site, in Kenya’s Turkana Basin, which shows that early hominins maintained a stable tradition of stone tool manufacture during one of the planet’s most unstable climatic periods

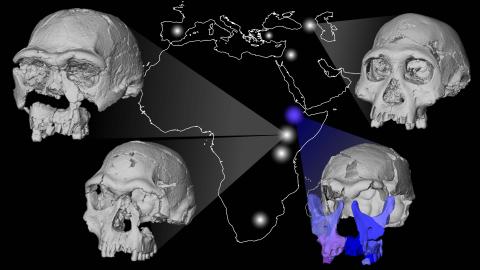

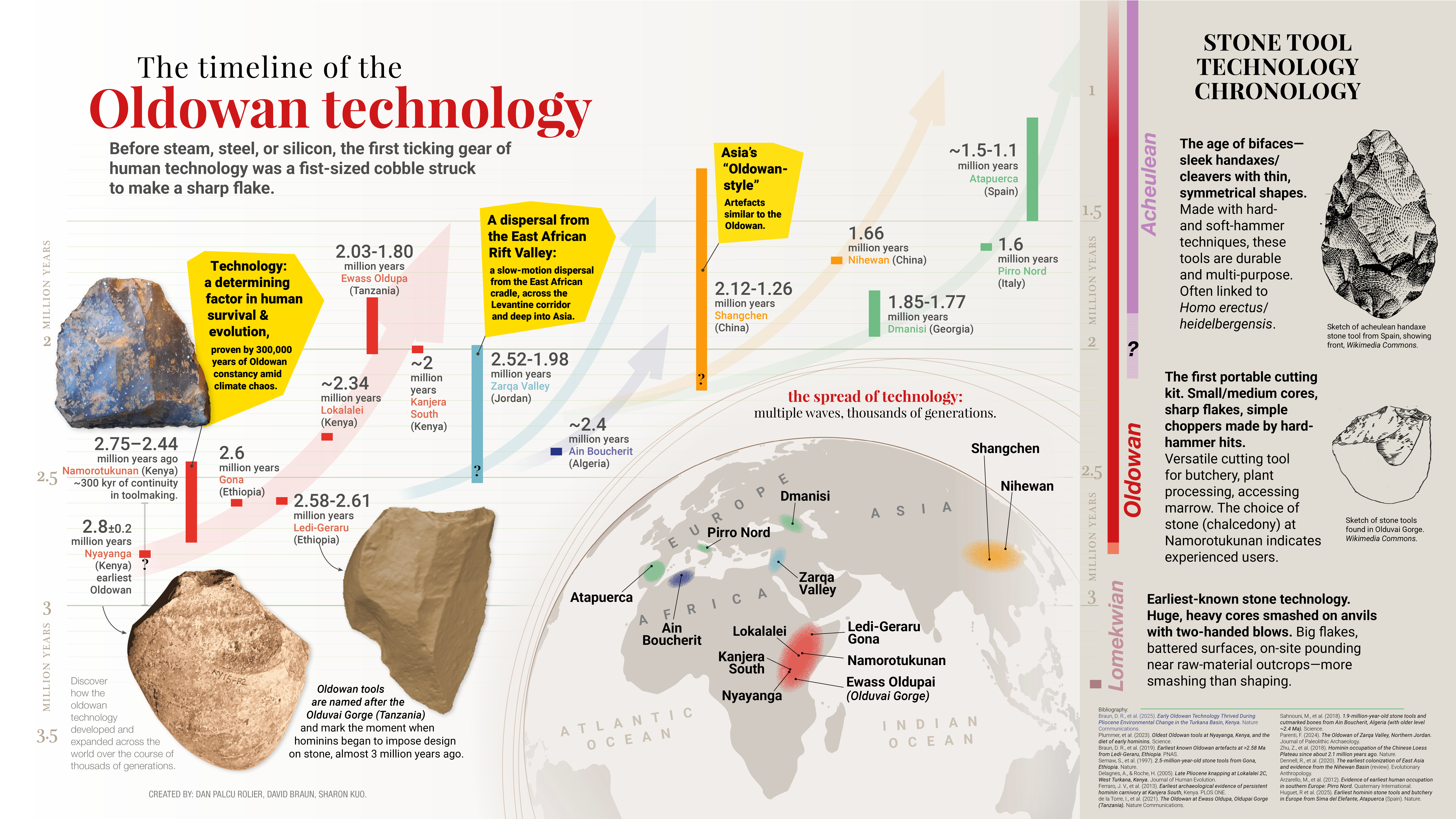

The Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH), participates in a study just published in Nature Communications by an international research team that has uncovered, at the Namorotukunan site in Kenya’s Turkana Basin, one of the oldest and longest sequences of early Oldowan stone tools, dated between 2.75 and 2.44 million years ago.

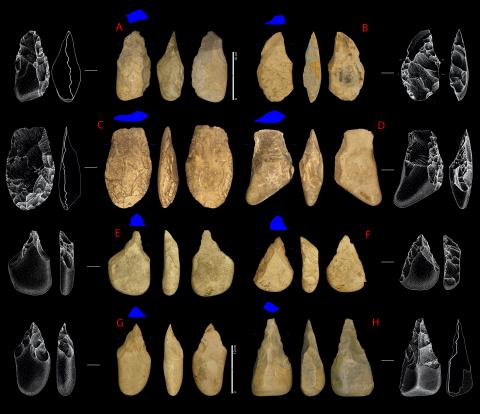

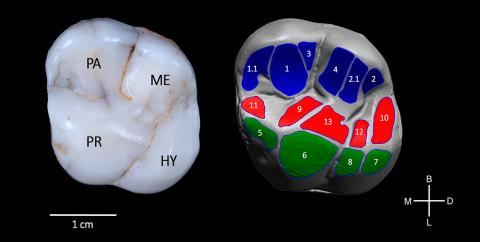

At this site, the authors have documented a continuous presence of stone toolmaking. The analysis of these artifacts reveals remarkable technical consistency, showing that by 2.75 million years ago, hominins already mastered the production of sharp-edged stone implements, suggesting that the origins of Oldowan technology are older than previously thought. These tools, considered humanity’s first “Swiss Army knives,” were used to cut, process food, and exploit both animal and plant resources.

The discovery demonstrates that early hominins maintained a stable stone-knapping technology for more than 300,000 years, despite facing recurrent wildfires, droughts, and drastic environmental changes. According to David R. Braun (George Washington University / Max Planck Institute), lead author of the study, Namorotukunan reveals an extraordinary story of behavioral stability and cultural continuity, representing not a single innovation but a long-lasting technological tradition.

Co-author Susana Carvalho (Gorongosa National Park, Mozambique) highlights that these results suggest tool use may have been a widespread adaptation among early human primates, transmitted from generation to generation.

Dating at CENIEH

The dating work, carried out in the Archaeomagnetism Laboratory of CENIEH, was a key part of this study. According to the geocrhronologist Mark J. Sier, (affilaited with CENIEH until 2024) “We applied advanced dating techniques combining volcanic ash chronology, magnetic signals preserved in ancient sediments, geochemical analyses, and microscopic plant remains to reconstruct the environmental evolution of the Turkana Basin. The result is a detailed picture of the relationship between technology and climate in the origins of humankind.”

Namorotukunan provides a unique geological window into a constantly changing world, where rivers, wildfires, and arid conditions repeatedly reshaped the landscape. Yet hominins preserved their toolmaking skills, demonstrating profound cultural resilience in the face of environmental challenges.

Teamwork

his study was led by a consortium of archaeologists, geologists, and paleoanthropologists from institutions in Kenya, Ethiopia, the United States, Brazil, Germany, India, the Netherlands, Portugal, Romania, Spain, South Africa, and the United Kingdom. Fieldwork was carried out under the supervision of the National Museums of Kenya and with the support of the Daasanach and Ileret communities.

The research received funding from the U.S. National Science Foundation (NSF), the Leakey Foundation, the Palaeontological Scientific Trust (PAST), the Dutch Research Council (NWO), the São Paulo Research Foundation (FAPESP), the American Museum of Natural History, and the Romanian National Authority for Scientific Research (PNRR).