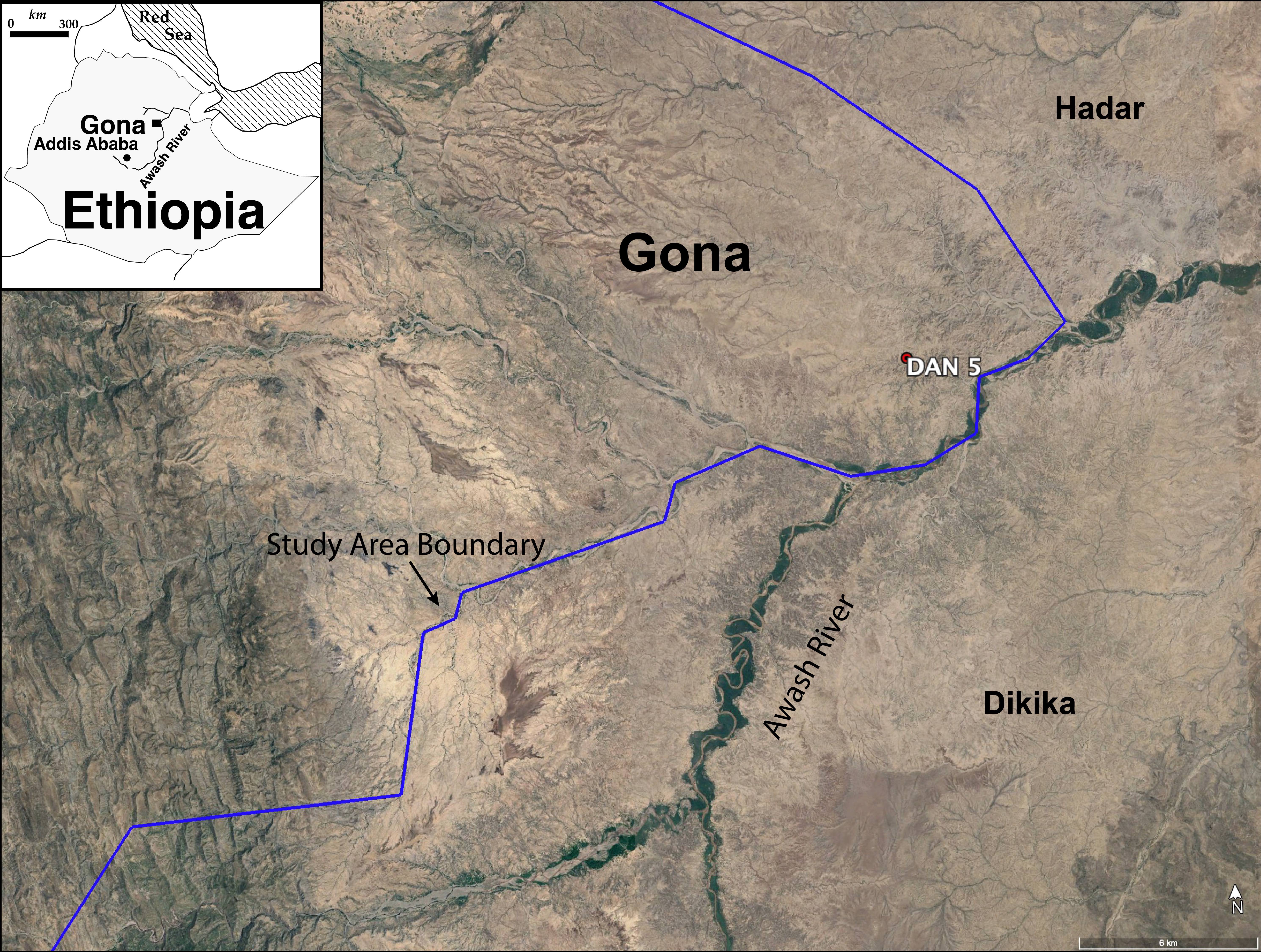

CENIEH is part of an international team that has presented a virtual reconstruction of a 1.5-million-year-old fossil face recovered at the site of Gona, in the Afar region of Ethiopia, which reveals new details about the first hominin species to disperse beyond the African continent.

Archaeologist Sileshi Semaw, a researcher at the Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH), is part of an international team that has just published a paper in Nature Communications presenting the virtual reconstruction of the face of a Homo erectus individual discovered at the Gona site, in the Afar region of Ethiopia. This fossil yields new insights into the first species to spread across Africa and Eurasia.

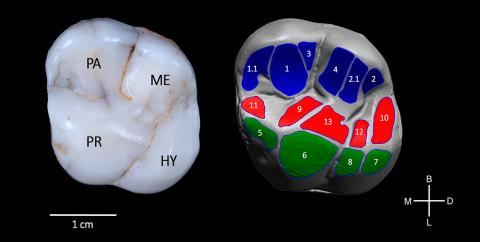

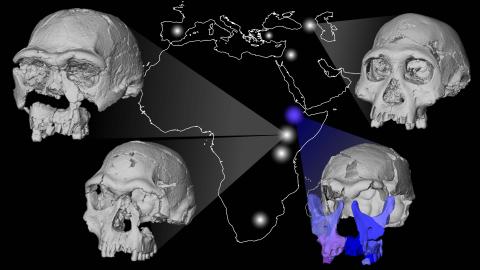

The virtual reconstruction includes a fossil cranial vault, teeth, and small facial fragments belonging to a single individual, known as DAN5. Together, these elements reveal a beautifully preserved and surprisingly archaic face dated to between 1.5 and 1.6 million years ago. This specimen represents the first complete Early Pleistocene hominin cranium recovered from the Horn of Africa.

This new study forms part of the Gona Paleoanthropological Research Project, co-directed by Sileshi Semaw and Michael Rogers (Southern Connecticut State University, USA), and is led by Karen Baab, a paleoanthropologist at Midwestern University, Arizona (USA). The results show that the Gona population at this time displayed a mix of typical Homo erectus characters concentrated in the braincase, together with more ancestral facial and dental features, such as a flat nasal bridge and large molars, traits normally observed in earlier species.

According to Karen Baab, “we already knew that the DAN5 fossil had a small brain, but this new reconstruction shows that the face is also more primitive than classic African Homo erectus of the same antiquity.” A similar combination of traits had previously been documented in Eurasia, but this is the first fossil to show this combination within Africa, challenging the idea that Homo erectus evolved outside the continent. One possible explanation is that the Gona population retained the anatomy of the population that originally migrated out of Africa approximately 300 thousand years earlier.

Digital reconstruction

The researchers used high-resolution micro-CT scans of the four major fragments of the face recovered during the 2000 fieldwork at Gona. Three-dimensional models of the fragments were generated from the scans. The facial fragments were then re-pieced together digitally, and the teeth were fit into the upper jaw where possible. The final step was “attaching” the face to the braincase to produce a mostly complete cranium.

This reconstruction took about a year and went through several iterations before arriving at the final version. Karen Baab, who was responsible for the reconstruction, describes the process as “a very complicated 3D puzzle, and one where you do not know the exact outcome in advance.” She adds, “fortunately, we do know how faces fit together in general, so we were not starting from scratch.”

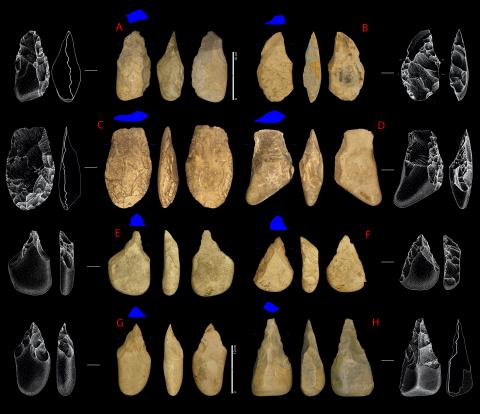

Oldowan and Acheulean

Along with anatomical diversity, behavioral diversity has also been documented at the Gona site. In this regard, Sileshi Semaw observes that “it is remarkable that the Homo erectus represented by DAN5 was making both simple Oldowan stone tools and early Acheulean handaxes, among the earliest evidence for the two stone-tool traditions to be found directly associated with a hominin fossil.”

Researchers in the field generally consider the Acheulean (Mode 2) to have replaced the earlier Oldowan (Mode 1) by around 1.7 million years ago; however, “our research at Gona has shown that Oldowan technology actually remained ubiquitous throughout the entire Stone Age,” explains the CENIEH archaeologist.

Future research

The researchers hope to compare DAN5 with the earliest human fossils from Europe, including fossils assigned to Homo erectus as well as to a distinct species, Homo antecessor, both dated to around one million years ago. “Comparing DAN5 with these fossils will not only deepen our understanding of facial variability within Homo erectus, but also shed light on how the species adapted and evolved,” explains Sarah Freidline (University of Central Florida), a co-author of the study.

There is also potential to evaluate alternative evolutionary scenarios, such as genetic admixture between two species, a phenomenon documented in later human evolution among Neanderthals, modern humans, and Denisovans. It is possible that DAN5 represents the result of admixture between classic African Homo erectus and the earlier species Homo habilis. As Michael Rogers notes, “we are going to need many more fossils dated between one and two million years ago to sort this out.”.