CENIEH contributes to an international study showing how major environmental changes in the past transformed large herbivore communities—and how, despite mass extinctions, ecosystems managed to retain their structure

IIgnacio A. Lazagabaster, researcher at the Centro Nacional de Investigación sobre la Evolución Humana (CENIEH), is part of the international team behind a pioneering study just published in Nature Communications. The study reveals how large herbivores—from mastodons to ancient rhinos and giant deer—have shaped terrestrial landscapes for millions of years, and how their ecosystems remained cohesive despite abrupt environmental disturbances, even when some species vanished.

The research team analyzed fossil records of over 3,000 species spanning 60 million years, using network analysis to trace changes in traits such as body size and tooth shape across continents and through time. This functional approach allowed them to understand how ecosystems worked, beyond simply identifying which species were present.

As lead author Fernando Blanco of the University of Gothenburg explains, the findings paint a picture of large-scale ecological stability. “We found that these ecosystems stayed remarkably stable over long periods of time, even as species came and went.”

Two major global disruptions

However, this long-term stability was interrupted by two global tipping points—episodes of extreme environmental change that permanently altered the ecological structure of large herbivore communities. “Twice in the last 60 million years, environmental pressure was so intense that the whole system reorganized on a global scale,” says Blanco.

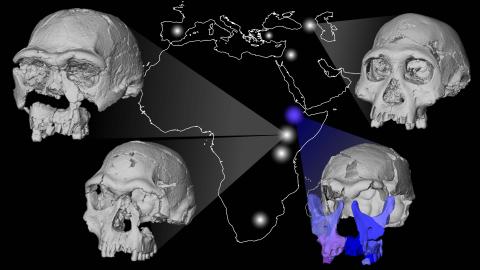

The first of these disruptions took place around 21 million years ago, when continental drift closed the ancient Tethys Sea and created a land bridge between Africa and Eurasia—the so-called Gomphotherium Land Bridge. This new corridor triggered a wave of migrations that reshaped ecosystems around the world.

Among these “travelers” were the ancestors of modern elephants, originally from Africa, which began expanding into Europe and Asia. But it wasn’t just elephants—deer, pigs, rhinos, and many other large herbivores also entered new territories, shifting the ecological balance.

The second global shift occurred approximately 10 million years ago, as Earth's climate grew cooler and drier. The expansion of grasslands and the retreat of forests favored grazing species with tougher teeth and led to the gradual disappearance of many forest-dwelling herbivores. This marked the onset of a prolonged decline in the functional diversity of large herbivores—the variety of ecological roles they fulfilled.

Fewer species, same structure

Despite these losses, the researchers found that the overall ecological structure of large herbivore communities remained surprisingly stable—even when some of the largest species, like mammoths and woolly rhinos, went extinct. The basic framework of ecosystem functions endured.

“It’s like a football team changing players during a match but still keeping the same formation,” says Ignacio A. Lazagabaster. “Different species came into play and communities changed, but they fulfilled similar ecological roles, so the overall structure remained the same.”

A long-term lesson

This resilience has lasted for the past 4.5 million years, surviving glaciations and other environmental crises up to the present. But the team warns that today's accelerated biodiversity loss, driven by human activity, could overwhelm the system.

Large herbivores are more than just consumers—they are “ecosystem engineers” that shape vegetation, disperse seeds, and influence everything from soil health to fire patterns. Their disappearance weakens entire ecosystems.

“Our results show that ecosystems have an amazing capacity to adapt,” says Juan L. Cantalapiedra, senior author and researcher at the Spanish National Museum of Natural Sciences (MNCN-CSIC). “But there’s a limit. If we keep losing species and ecological roles, we may soon reach a third global tipping point—one that we’re actively helping to bring about.”

Video